Chaharshanbe Suri is an ancient Zoroastrian festival celebrated by jumping over fire during the last week of the solar year. This traditional Iranian celebration occurs between Tuesday night and Wednesday, marking the end of winter. The word “Chaharshanbe” means Wednesday, while “Suri” refers to celebration. This festival is rooted in longstanding Iranian traditions that extend to neighboring countries such as Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Turkey.

Ancient Origins of Chaharshanbe Suri

Chaharshanbe Suri is one of the festivals observed during Hamaspathmaēdaya (Farvardigan), a five-day period dedicated to honoring the souls of the departed and the Amesha Spenta (the Seven Immortals in Zoroastrianism). Its origins trace back even further to the festivities surrounding Nowruz.

The Mesopotamian festival commemorating the return of Dumuzi (Tammuz) marked the transition from winter to spring. Dumuzi, the fertility deity, would descend to the underworld each year and return in springtime, heralding fertility and the agricultural season.

The original feast of Hamaspathmaedaya was established following calendar reforms by Ardashir I in the second century CE, initiating six days of observance before the new year, celebrating both fire and the creation of humankind by Ahura Mazda. During the Sassanid period, this festival evolved into two parts: the first honored the spirits of innocents and children, while the second recognized all spirits.

Some historical accounts suggest that Sassanid king Hormizd-Ardashir initiated the custom of lighting fires during Nowruz to purify the air and dispel evil spirits. This fire ritual may also have roots in the Zoroastrian Sadeh festival.

Chaharshanbe Suri After the Arrival of Islam

Following the Arab conquest of Persia, the observance became restricted to the last Wednesday of the year, as the preceding Wednesday was deemed unlucky in Arab culture. Lighting fires then took on a preventative role against misfortune. Many historians claim this shift influenced the contemporary rituals of Chaharshanbe Suri. In the Islamic era, the festival was moved to coincide with the last Wednesday of the lunar month of Safar instead of the solar calendar.

Some accounts connect the origins of Chaharshanbe Suri to the rise of Mokhtar al-Thaqafi or Abu Muslim’s uprising in Khorasan. There are also mentions of a Samanid ceremony featuring large bonfires known as Shab-e Suri, although detailed descriptions are scarce.

Regardless of its origins, Chaharshanbe Suri has endured in Iran for millennia and remains widely celebrated across the region. While its roots lie in Zoroastrianism, people from all backgrounds celebrate this occasion.

Chaharshanbe Suri Rituals in Iran

The festival comprises various supplementary rituals that may vary by region, but the common theme of all Chaharshanbe Suri practices is the lighting of fire.

Lighting a Fire

The central ritual of Chaharshanbe Suri involves igniting a large bonfire, typically in an open area. Historically, fires were lit on rooftops. It is said that after Mokhtar al-Saghafi was released from prison, he encouraged his supporters to light fires as a demonstration of loyalty.

Iranians often ignite three bonfires representing the three Zoroastrian principles of Humata, Huxta, and Huvarshta (Good Thoughts, Good Words, and Good Deeds). In some cases, they may light seven bonfires in honor of the seven Amesha Spenta (Zoroastrian divine beings).

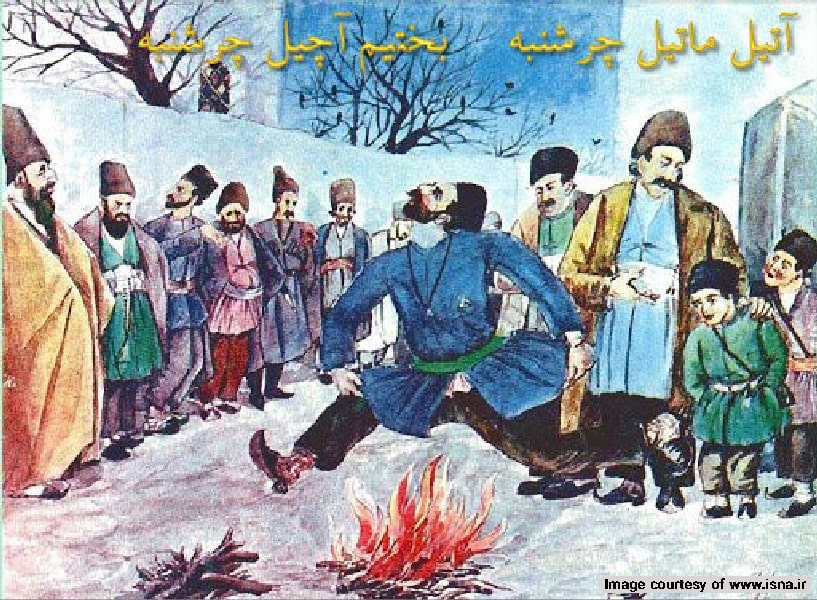

Jumping Over Fire

This purification ritual invites everyone to jump over the fire in a symbolic gesture to cast off bad luck. During this act, participants chant:

Zardi-ye Man Az To, Sorkhi-ye To Az Man

Take my yellowness, and I will take your redness

“Yellowness” symbolizes poor health (like jaundice), while “redness” embodies life and vitality. This ritual aims to rejuvenate one’s health for the forthcoming year.

The act of jumping over the fire became prominent during the Islamic period. In Zoroastrian beliefs, this could be seen as sacrilegious, as fire is revered as one of the four sacred elements.

Qashogh Zani (Spoon Banging)

This ritual represents one of the oldest customs of Chaharshanbe Suri. Unlike Halloween’s trick-or-treating tradition, participation is open to people of all ages. Men and women often wear disguises, typically donning a Chador (cloak) over their heads. This tradition symbolizes the return of spirits to the living realm during spring.

Participants visit seven homes while maintaining their anonymity. The Qashogh-Zan (spoon banger) keeps silent as they use a bowl and spoon to create a rhythmic banging sound. The host typically fills the bowl with legumes or sometimes money. This practice connects to another ritual of Chaharshanbe Suri.

In modern urban settings, this ritual is becoming less common, although some villages still preserve a variation where young boys wear Chadors and sing traditional songs while visiting houses.

Koozeh Shekani (Clay Urn Breaking)

A Koozeh is an unglazed clay urn traditionally used in Iranian households to store water and other consumables. Due to its porous surface, these urns cannot be cleaned thoroughly and often accumulate dirt by year’s end. Traditionally, it is believed these urns trap bad luck and evil spirits.

On the last Wednesday night of the year, households would drop their old urn from the rooftop or break it through other means. In some regions, people break urns after jumping over the fire, while in Khorasan, they might place coal, salt, and a coin inside the urn, spin it over each family member’s head, and then break it.

Fal Giri (Fortune-Telling)

Fal Giri is a popular social ritual associated with Chaharshanbe Suri, where fortune-telling is practiced. One unique method is called Fal-e Boolooni, which involves a small jar used for pickling goods. Each participant places a note containing a poem and a personal item into the jar. A child then selects one note and item, and the poem reveals the fortune of the item’s owner.

Another traditional fortune-telling method is Fal-e Goosh, where young girls make a wish, hide behind a wall, and listen in on strangers’ conversations, taking their words as responses to their wishes.

Shawl Andazi (Scarf Throwing)

This traditional custom, still observed in some villages and towns in Hamadan and Zanjan, involves young people tying several scarves or shawls together to create a long rope. They then slide this rope down chimneys or over walls, calling attention to themselves through coughing. The homeowner responds by placing gifts into the shawl and tying it closed.

The gifts serve both as presents and a form of fortune-telling. For example, bread signifies prosperity, sweets suggest happiness, and pomegranates denote fertility. Items like walnuts symbolize longevity, while hazelnuts and almonds indicate persistence and patience. Raisins forecast adequate rainfall, silver coins may signify an upcoming marriage, and in some regions these can imply a discreet marriage proposal.

Bakht-Gosha (Untying Luck)

In traditional beliefs, a girl without suitors is said to have her luck tied up. This ritual varies by region and includes a series of superstitious practices involving locks, knots, threads, and walnuts, all aimed at untying the girl’s fated luck and assisting her in finding a husband in the new year. This practice extends into the Sizdah Be Dar celebration, where girls tie grass strands into knots to ward off bad luck.

Chaharshanbe Suri Foods

Families in Iran prepare several special dishes on the last Wednesday of the year, with recipes varying regionally to reflect traditional beliefs.

Ajil-e Chaharshanbe Suri (Mixed Nuts)

Ajil-e Chaharshanbe Suri is a mixture of nuts and dried fruits, often called Ajil-e Moshkel Gosha in places like Khorasan, meaning “problem solver” or “wish granter.” It typically contains unsalted nuts and dried mulberries or prunes, said to bring good fortune.

Ash-e Abudurda (Ashe Shafa)

In certain regions, people prepare a special soup on this night made from a mixture of legumes (beans, lentils, and chickpeas), along with vegetables and noodles. It is reminiscent of Ashe Reshteh but incorporates flour dough figurines of Abudurda, believed to have healing properties.

Modern Chaharshanbe Suri Practices

Today, Iranians continue to celebrate this festival annually, often with large community bonfires and fireworks. Many gather in their neighborhoods to light fires, jump over them, play music, and dance with family and friends.

Unfortunately, some young people resort to illegal or improvised fireworks, which can pose significant risks, leading to injuries or even fatalities. This has led to the colloquial nickname Chaharshanbe Suzi (Burning Wednesday). The government prohibits the sale or use of such fireworks, and emergency services remain vigilant during Chaharshanbe Suri to prevent fire hazards in urban areas.

Chaharshanbe Suri in Iranian Culture

The ancient tradition of Chaharshanbe Suri is referenced by Ferdowsi in the Shahnameh during the tale of Bahram Choobineh and Parmoudeh. An astronomer cautions Bahram to avoid Wednesday due to its associations with bad luck and ignites a fire to drive away evil spirits.

Additionally, this festival connects to the legend of Siavash, who, in his trial by fire, asserted his innocence through the act of walking through flames. The Zoroastrian priests valued fire for its ability to differentiate good from evil, and some believe that the fire-jumping tradition is a celebration of Siavash’s purity.

Participate in the Chaharshanbe Suri Festival in Iran

Traditional Iranian festivals are crucial components of our intangible cultural heritage. By participating in these rituals, you can gain deeper insights into Iranian culture and customs. If you’re in Iran around the last days of the solar year (mid-March), consider joining the Chaharshanbe Suri celebrations. Remember to prioritize safety and avoid hazardous fireworks.

Frequently Asked Questions About Chaharshanbe Suri

If you have any questions about the Chaharshanbe Suri celebration or other ancient Iranian festivals, please leave a comment, and we will respond promptly.

What is Chaharshanbe Suri?

Chaharshanbe Suri is an ancient Persian festival observed on the evening of the last Wednesday before Nowruz, the Persian New Year. It honors the arrival of spring through a series of rituals, notably fire-jumping.

What are the main traditions of Chaharshanbe Suri?

Main traditions include lighting bonfires, jumping over them with chants to symbolize the purification of the soul, and setting off fireworks. Participants also decorate their homes and gather in community celebrations.

What does jumping over fire symbolize?

Jumping over fire signifies the release of negativity, illness, and misfortune. The fire acts as a purifying force, incinerating harmful influences from the past year to welcome health and brightness into the new year.

What do people say when jumping over the fire?

During the fire-jumping tradition, individuals often chant phrases such as “Zardie man az to, sorkhi to az man,” meaning “My paleness is yours, your redness is mine,” signifying an exchange of health and fortune.

Are there any specific foods associated with Chaharshanbe Suri?

Yes, traditional foods include various snacks and sweets, such as “Ash-e Chaharshanbe Suri,” a herb soup, and a special mix of nuts and dried fruits called Ajil-e Moshkel Gosha (wish-granting mixed nuts) shared among family and friends.

How is Chaharshanbe Suri celebrated in different regions?

While core rituals remain constant, different regions may showcase unique customs. In some areas, people create intricate bonfires, while others may engage in street fairs or choreograph firecracker displays.

Is Chaharshanbe Suri celebrated only in Iran?

Although it is primarily celebrated in Iran, variations of this festival can be observed in other nations with Persian cultural influences, including Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and parts of Central Asia.

Are there any safety concerns during Chaharshanbe Suri?

Indeed, safety is paramount. Participants should exercise caution while jumping over fires and handling fireworks to prevent injuries or disasters. Maintaining a safe distance and ensuring fires are monitored is essential.