While many people flock to Australia’s stunning beaches and vibrant cities, the Outback may appear to hold little interest. However, we invite you to look again, as the Outback is rich in life, hosting a dazzling variety of wildlife, around 1,500 communities, including the Anangu people, and the sacred Uluru, a monumental rock that serves as the soul of Australia. Join us as we delve into Liz’s incredible adventure responding to the call of Uluru.

Sir Alec Issigonis, the creator of the Mini, famously remarked that a camel is a horse designed by committee. What might he have said about a kangaroo? Surprisingly, Australia’s iconic animal isn’t even the most intriguing of its creatures. Astonishingly, over 80% of Australia’s plants, mammals, reptiles, and frogs are unique to the continent. Charles Darwin, who never actually encountered a kangaroo, described “the peculiar nature of the animals in this country compared to the rest of the world.”

Exploring Australia’s Outback

Australia itself is as unique as its wildlife. It stands as the lowest, flattest, and oldest continental landmass on Earth. While a majority of the population relaxes on picturesque beaches and enjoys modern city life, the vast expanse of the Outback—stretching over 2.5 million square miles—offers a very different narrative. Often referred to as The Bush, the Outback receives only 20 inches of rain each year, resulting in a sparse landscape. My somewhat irreverent Great Uncle Bob, who migrated to Australia after World War I, coined the term GABA – the Great Australian Bugger All – a phrase that has endured through time.

Despite initial impressions, the Outback thrives with diverse wildlife, including red kangaroos, wallabies, dingoes, skinks, frilled-neck lizards, and more. Additionally, around 1,500 communities, mostly Indigenous, have made this vast area their home for thousands of years. The Anangu people have inhabited the region surrounding Uluru for about 40,000 years, regarding the giant rock as a sacred site.

Uluru: The Sacred Heart of the Outback

Uluru, also known as Ayer’s Rock, rises dramatically from the surrounding sand and sparse vegetation. During the lengthy four-hour bus ride from Alice Springs, the scenery appears dull. Yet, when the driver, Martin, makes a stop seemingly in the middle of nowhere, he gestures toward a sandhill, instructing us, “Go up there.”

The heat is intense, but a few of us climb out of the air-conditioned bus to ascend the dusty path. What awaits us is nothing short of spectacular!

Before us stretches what resembles a winter wonderland, but the hot sand beneath my feet is a stark reminder of the region’s climate. Martin explains that this is one of the numerous salt lakes in the area, the largest being Lake Amadeus, situated just north of Uluru, spanning over 1,000 square kilometers. “This was once part of an inland sea, which is why the groundwater here is salty,” he adds. “In fact, in some areas, the salt crust is so thick that vehicles can drive on it.”

Already convinced that this long bus ride was worthwhile, Martin stops once more, and for the first time, I see Uluru in the distance, resembling a giant loaf of bread fresh from the oven. Towering at 348 meters (1,140 feet) and encircled by 9.5 kilometers (6 miles), Uluru is the world’s largest sandstone monolith, dominating the landscape even from afar.

Located 19 kilometers from Uluru, the sister formation, Kata Tjuta, comprises 36 colossal domes spread over more than 20 kilometers (12 miles). This grand pair of landmarks holds significant spiritual value, converging with numerous Indigenous creation narratives. The Australian government has recognized this importance; in 2000, the Olympic torch’s journey began by circling the base of Uluru, and a ban on climbing the rock was enforced in 2019, affirming its sacred status.

Pioneering a climb up Uluru was once a popular challenge for many travelers. It was a demanding ascent of 1.6 kilometers, and with no restroom available, many chose the top for relief. Most Indigenous people deemed this behavior disrespectful, comparing it to desecrating an important Buddhist temple, mosque, or church. It’s important to note that many climbers have been injured, and some even lost their lives attempting the climb. The Anangu people bear sadness over the visible scar left behind on the rock from this activity, requesting that it not be photographed.

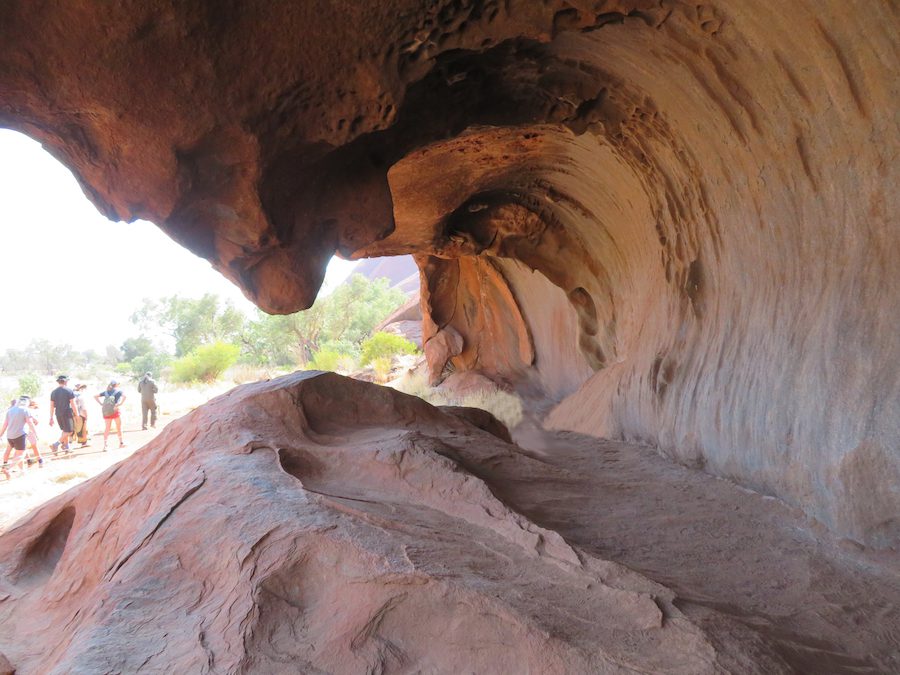

Today, walking tours around the base of Uluru are available with Indigenous guides. Our guide highlights a deep waterhole replenished by a waterfall at the base, known as the “Sacred Waters,” which has supported desert-dwelling animals and the Aboriginal community for millennia.

While the environment can be harsh, the Anangu have learned to thrive here. An elder shares, “We don’t try to control the world; we live in it and adapt.” This perspective stems from their respect for nature and a commitment to protecting it.

At the base of Uluru lie caves and crevices designated for specific purposes. One serves as a kitchen, another is the men’s area, and yet another is sacred to women. Their social structure is profound, with rock art estimated to be 12-14,000 years old. The elder explains, “Our religion was never written down; our elders keep the stories alive.”

The Anangu people believe that the unique geological shapes and features in Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park hold wisdom and stories still relevant today. One ancient narrative involves the Mala people settling near Uluru and the devil dog Kurpany, who sought to destroy them. This story, transformed into a contemporary retelling, is a highlight of my visit to Uluru.

Wintjiri Wiru: Sharing the Ancient Mala Story

In May 2023, Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia launched Wintjiri Wiru, which translates to “beautiful view out to the horizon” in the local Pitjantjatjara language. This remarkable, immersive light and sound experience employs over 1,100 drones to narrate the ancient Mala creation story, marking the first time such an exhibition has been presented regularly on this scale anywhere in the world.

Our journey begins on a terrace nestled in the bush, providing stunning views of the setting sun illuminating Uluru in one direction and Kata Tjuta in another. I enjoy a refreshing cucumber cooler infused with Beachtree Gin (from an Indigenous-owned distillery) and savor unusual appetizers: mini sweet potato flan topped with wattleseed crumbs; ginger-flavored cucumber spears with green ants; and lemon myrtle crocodile curry tarts.

As the sky darkens, the colors shift wonderfully. We collect our food hampers filled with incredible flavors and find our seats in an amphitheater built into a natural hollow, decorated with traditional Indigenous designs.

I watch as Uluru fades into the night, savoring local cheeses, blackened pepper leaf kangaroo, shrimp Waldorf salad, smoked emu with a chili crust, and jams made from quondong and Davidson plum. For dessert, I sample a lime tart topped with green ants. Yes, I taste everything—even the ants!

However, as night falls, the food fades into the background. A full moon rises on the horizon, transforming the land before me into ocean waves, glowing flames, while the gripping story of Mala unfolds. A colossal Kurpany, formed from dozens of drones, towers above us. The narrative is recounted in both Pitjantjatjara and English, accompanied by powerful, haunting music.

As the last drones vanish, replaced by a star-studded desert sky, the radiant moon seems to resonate with the melodies. Uluru, a stoic presence in the distance, remains timeless and enduring.

Before dawn, I trek to the lookout near the Outback Hotel to witness the two monolithic formations greeted by the first rays of the sun. Alone in this vast wilderness, I feel the weight of their grandeur as they dominate the landscape. Nearby, I hear the rustle of a desert creature and silently hope it’s not a venomous snake I’ve disturbed; after all, Australia is famed for its dangerous reptiles. Fortunately, it retreats as I continue on, for breakfast awaits and later, a bus back to Alice Springs.

I leave with memories of scorching red sand, sparse shrubs, breathtaking sunsets, and a deep night sky brimming with stars—these ancient behemoths capturing my gaze.

This profound area holds immense significance for the Indigenous people who have lived here for thousands of years. It is a remarkable experience to walk on this land, to listen to the stories of its long-time inhabitants, and to stand in awe before a monolith so vast, it extends 2.5 kilometers below the surface. This is the very heart of Australia, often dismissed as ‘bugger all,’ yet its pulse remains vibrant and strong.

Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links. Should you make a purchase after clicking on one of these links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. This commission helps support our writers’ storytelling efforts. We only endorse products we personally have tried.